The foundation of imitation learning is a Markov Decision Process which satisfies the Markov property. The Markov property is a chain of state sequences x₁, x₂, … xₜ where the next state xₜ only depends on the current state xₜ₋₁. A Markov Decision Process contains a set of possible world states S, a set of possible actions A, a reward function R(s, a) and a description T of each action's effects in each state (Givan and Parr, 2001). Each state and action specify a new state

T: S × A → S

and each state and action specify a probability distribution for all the other states

T: S × A → P(s' | s, a).

In imitation learning the machine takes an input of expert demonstrations or trajectories

𝜏 = (s₀, a₀, s₁, a₁, …)

where the state-action pairs are formed based on the expert's optimal π* policy. To follow a policy π the machine determines the current state S and executes an action π(s). This process is then repeated.

Behavioral cloning is the simplest form of imitation learning and it works by directly mapping from states/contexts to trajectories/actions without recovering the reward function (Osa et al., 2018). These methods treat state-action pairs as independent and identically distributed variables and learn policy π through supervised learning and minimizing the loss function.

Behavioral Cloning in a

Self-DrivingToy Car

Made with Raspberry Pi  &

controlled by a convolutional

neural network auto-pilot

&

controlled by a convolutional

neural network auto-pilot

Building Blocks

The architecture of autonomous systems in self-driving cars primarily comprises two essential components: the perception system and the decision-making system.

The perception system is responsible for detecting traffic signals, mapping roads, and identifying the car's position, speed, direction, and state using various sensors. On the other hand, the decision-making system handles route and path planning, steering, and throttle, making it possible to respond effectively to any situation in real-time (Badue et al., 2019).

The decision-making system relies on advanced software algorithms capable of handling multiple simple and complex driving scenarios seamlessly. These algorithms utilize data gathered by the perception system to train machine learning models which enable the car to make informed decisions.

One type of such algorithm is reinforcement learning, which enables an agent to learn how to behave in an environment by

performing actions and receiving feedback in the form of rewards or penalties. The goal of reinforcement learning is to learn a policy, which is a set of rules that the agent can use to make decisions, in order to maximize its long-term reward (Peter Stone, 2010). Tokens of reward or punishment are manually specified, such as negative 50 points when the car drives off the road and steps onto the sidewalk during training. Over time, the car learns to avoid such behavior, thus making driving safer.

However, designing a reward system such as this can be incredibly complex due to the wide range of factors at consideration when it comes to car and road safety. An alternative approach is Imitation Learning, where an expert driver provides a set of demonstrations such as driving around a track several times. The model then learns the optimal policy by imitating the driver's decisions and behavior. Imitation learning is most commonly used when it is easier for an expert to demonstrate the desired behavior than it is to manually specify actions that should be rewarded or punished (Zoltán Lőrincz, 2019).

Imitation Learning

RC Self-Driving Car

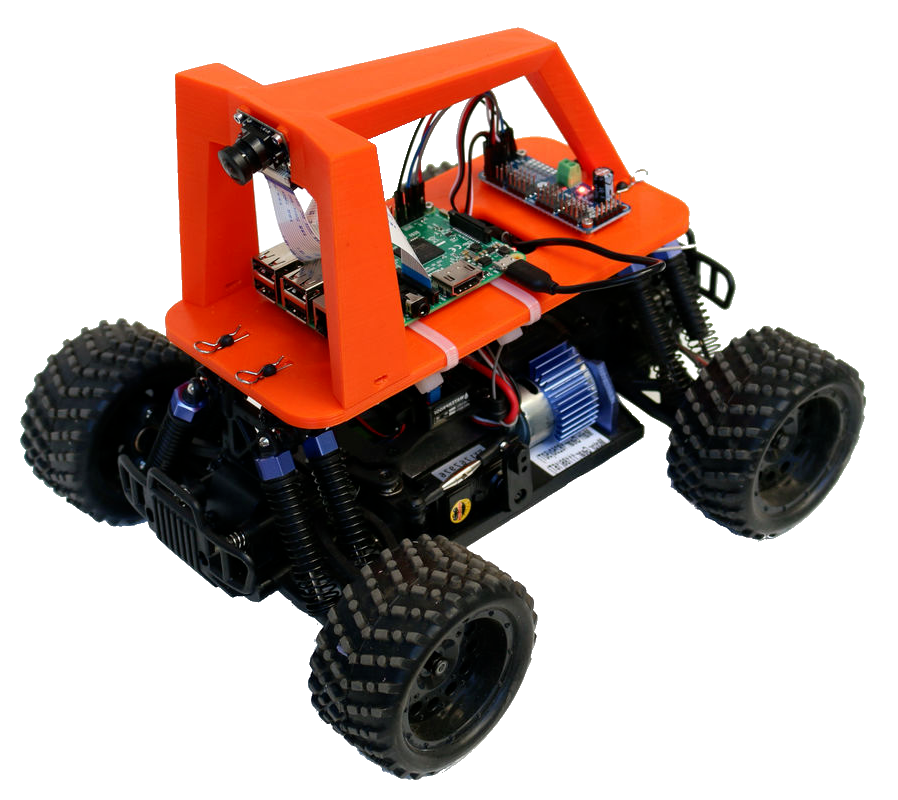

To further examine the application of behavioral cloning in self-driving cars, I resolved to put theory into practice. The prospect of constructing a fully functional autonomous vehicle and testing it on the open road was not only impractical, but also ridiculously dangerous and highly illegal. I opted to work with a remote-controlled toy car, equipping it with a Raspberry Pi and a convolutional neural network auto-pilot. Donkeycar, a Python-based library for self-driving, provided the ideal platform for this endeavor.

The car of choice was an Exceed Magnet RC toy. Steering and throttle were controlled by a servo, and images recorded using a wide-angle Raspberry Pi camera. All of the other hardware parts were obtained through Donkeycar kits. I made an elliptical race course for the car on the floor of my living room using black masking tape.

The car was initially controlled through a web interface using a

gamepad, joystick or device tilt. The configuration files dictated that when throttle is bigger than zero the camera automatically records 10 images per second. When training a model, these images were associated with steering and throttle actions which directly preceeded them. This is a concept similar to the state-action pairs described in the Markov Decision Process above. Therefore, data for training the behavioral cloning model is collected simply through driving around the track, preferably without steering off course. Any crashes or mistakes made are faulty data which can negatively impact the model's performance so they have to be eliminated prior to training.

After the model was trained using Keras and TensorFlow 2.0, choosing the local pilot option on the web interface allows the auto-pilot to control both steering and throttle. Alternatively, setting the throttle to a certain value and choosing the local angle option allows the auto-pilot to control only steering.

Benefits

I was able to investigate two strengths of behavioral cloning through my project.

- Efficiency - The model quickly learns and is able to achieve a fairly high accuracy given the time spent training and the size of the dataset.

- Simplicity - The architecture of the model is fairly straightforward and can be understood even with no prior knowledge of convolutional neural networks.

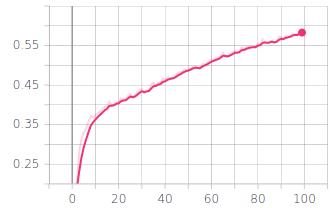

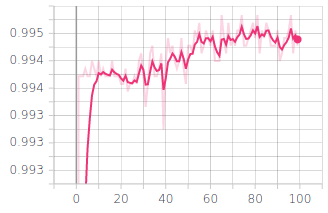

In both graphs, the x axis represents the training time over 100 epochs. Evidently, the model achieved relatively high values of accuracy fairly quickly in the training process. Throttle was especially well learnt and the accuracy value for the steering angle, although lower than the throttle one, is still quite impressive.

This is one strength of behavioral learning; the model is able to quickly learn how to reproduce the demonstrated behavior and apply it to the validation dataset. The entire process of training this model lasted less than 3 minutes on a GPU. Arguably, it is a simple model in comparison to complex software used by autonomous vehicles in the real world, but this is a good example of how accessible and efficient behavioral cloning is on a smaller scale.

Steering Angle Accuracy over Training

Throttle Accuracy over Training

Additionally, behavioral cloning is arguably easier to understand than most other learning techniques. The convolutional neural network used for this auto-pilot takes in an input of images, and actions associated with them. When trained with a sufficient amount of data, these networks can accurately identify what triggered those actions based on the recordings. For example, if the goal is to remain on track, the CNN will recognize that every time we approach the black line on the left side we steer right. The model is then designed to use the trained neural network and reproduce the steering and throttle given the image recorded by the camera.

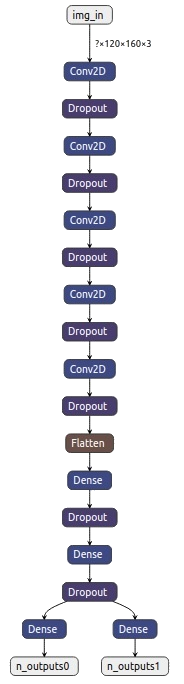

To obtain a visual representation of the trained CNN (shown on the right), I used Netron, a tool specifically designed for visualizing machine learning and deep learning models. Convolutional neural networks consist of input, output and several hidden layers. If we read the diagram from top to bottom, we see the first element is the input in the form of tensors of images recorded by the car's camera. The Conv2D layers are convolutional layers and they apply a filter to each image they take in and scan it pixel by pixel. The image is then abstracted to a feature map. This tends to create a lot of data, some of which proves to be useless. This is why the Dropout layers scale down the amount of information generated by convolutional layers, and keep only the most important data points in a process known as downsampling. A convolutional layer followed by a downsampling layer occurs 5 times in this model. This ensures that input images are stripped down to the most important features that dictate steering and throttle. The Flatten layer takes the outputs of the previous layers, and turns them into a single vector. Now the dense layers determine how important each feature in an image is, and add 'weight' to them accordingly (Wikipedia, 2020). The output layers finally generate probabilities and produce an accurate classification of an appropriate action.

This is how behavioral cloning models learn. Understanding the function of each layer is fairly straightforward, and that is another one of the strengths of this method. For one, simplicity allows for easier modification of the model according to the needs of the particular application. Furthermore, if an issue is to arise, we can more easily determine which layer caused the mishap.

Limitations

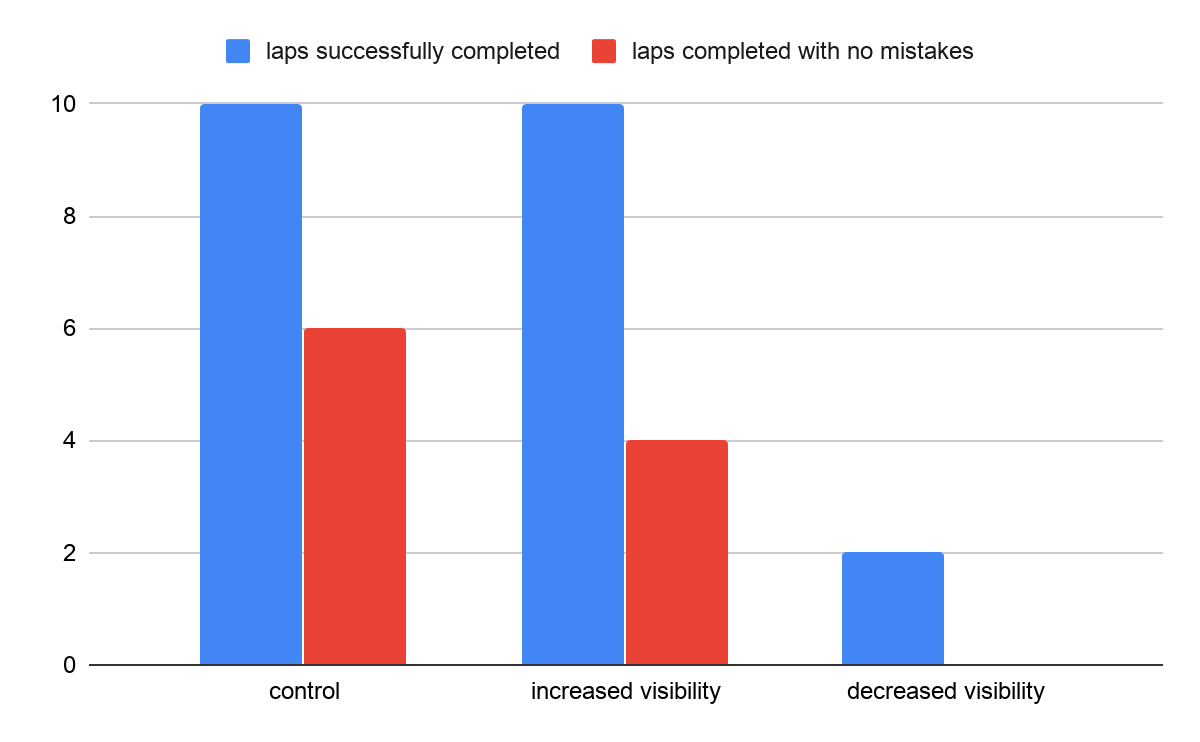

The disadvantage of behavioral cloning lies in the bias of the training dataset. This was easy to demonstrate in my case. During driving demonstrations, I ensured there was no natural light in the training environment because I wanted to minimize the effect of variable environmental circumstances. This means that my car would likely perform worse in an environment with less or even more light. I decided to test this hypothesis by letting the car drive around the track 10 times using the trained model, under one of three conditions:

- No natural light, but the track is well lit by lamps - control

- Both natural and artificial light - increased visibility

- No natural and minimal artificial lights - decreased visibility

Count of successful vs unsuccessful laps per condition

The first condition, closely matching training conditions, allowed for the best model performance. The model performed slightly worse in increased visibility, and decreased visibility had a much worse effect on the model - the car only finished two laps without crashing into surrounding objects or fully stopping.

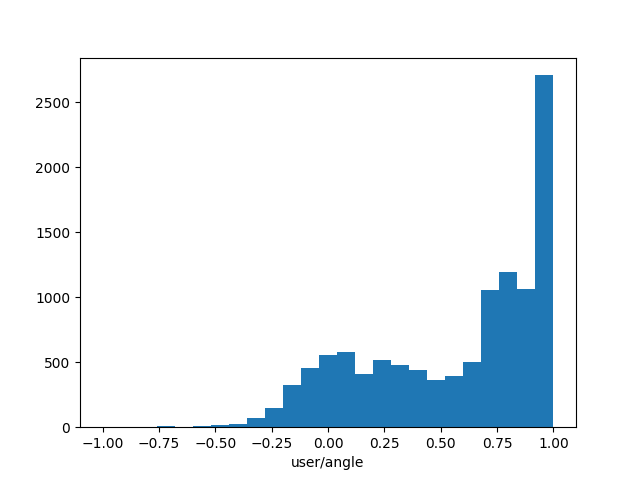

Additionally, the race track I made for the car is elliptical and doesn't have any unusual curves or obstacles. Whenever I drove the car I always assumed it should follow clockwise motion around the track. This means that the car almost exclusively made right turns and the steering was strongly biased in that way. In order to examine this I extracted the steering angle data from more than

10000 images in the training dataset and plotted a histogram using matplotlib - a Python library for visualization.

Steering angle in training instances

A value of -1 on the x axis represents a far left turn, and a value of 1 represents a far right turn. Evidently, the model is biased towards right turns. As a consequence, the car wasn't able to react appropriately in situations which require a left turn. Indeed, when attempting to put the car in a different starting position and change the direction of the motion in order to observe its response, the car immediately steered off course and crashed into nearby objects. It was not able to complete a single lap. In fact, it was not able to make a noticeable left turn at all.

Although these are very banal examples, they illustrate how dependent behavioral cloning is on consistent environmental conditions. Issues caused by biased datasets can be addressed through demonstrations performed in a variety of conditions, or data augmentation. However, models are likely to misbehave when in a situation which they have never seen before. This calls for additional expert demonstrations or manual specification of appropriate responses to certain cases. None of these solutions are ideal and would likely cause severe consequences in the real world.

End of the Road Discussion

Over the course of this project, I explored both the positives and the negatives of behavioral cloning. This has, at times, made me wonder whether behavioral cloning should be considered artificial intelligence due to its imitating nature, dependence on the training dataset, and inability to appropriately react in situations not demonstrated during training. Although it is a useful method for many use cases, and worked incredibly well for my purposes, it is by no means a technique which would work well on its own when implemented in an autonomous vehicle. It is efficient and straightforward, but it could benefit from working alongside a reinforcement learning model and manually specified policies in order to make up for its drawbacks.

References

Badue, C., Guidolini, R., Carneiro, R., Azevedo, P., Brito Cardoso, V., Forechi, A., Jesus, L., Berriel, R., Paixão, T., Mutz, F., Veronese, L., Oliveira-Santos, T. and Ferreira, A. (2019). Self-Driving Cars: A Survey. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.04407.pdf [Accessed 28 April 2023] Stone, P. (2011). Reinforcement Learning. Encyclopedia of Machine Learning. [online] Available at: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-0-387-30164-8_714 [Accessed 28 April 2023] Lőrincz, Z. (2019). A brief overview of Imitation Learning. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@SmartLabAI/a-brief-overview-of-imitation-learning-8a8a75c44a9c [Accessed 28 April 2023] Givan, B. and Parr, R. (2001). An Introduction to Markov Decision Processes. [online] Available at: https://www.cs.rice.edu/~vardi/dag01/givan1.pdf [Accessed 28 April 2023] Osa, T., Pajarinen, J., Neumann, G., Bagnell, J.A., Abbeel, P. and Peters, J. (2018). An Algorithmic Perspective on Imitation Learning. Foundations and Trends in Robotics, [online] 7(1-2). Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1811.06711.pdf [Accessed 28 April 2023] Wikipedia Contributors (n.d.). Convolutional neural network. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convolutional_neural_network [Accessed 28 April 2023]